Frank Sinatra may have been Hoboken’s favorite son and Hollywood royalty—and we all know how well he sang about Chicago and New York, but he belonged to Las Vegas.

By Nina Fedrizzi for Wynn Magazine

Spend enough time in the company of Las Vegans of a certain age and you will almost certainly hear a Frank Sinatra story or two. They’re usually told in reverent tones, a memory passed down like some cherished family heirloom. Today the list of those who truly knew Sinatra during the Rat Pack’s golden age in the 1960s—first at the Desert Inn, where Wynn Las Vegas now stands, then holding court in the Sands’ Copa Room and Golden Nugget — is dwindling rapidly. But if you listen carefully, you can still hear the stories.

There are the tales of the palms he casually greased during late nights at the gaming tables, a drink and a smoke at hand. Or the stories of his extravagant generosity, such as the time he bumped into a just-married friend of a friend at the Sands and, with the snap of his fingers, got him the honeymoon suite, a free dinner, and a front table at the show that evening. And, of course, there are the well-worn Sinatra anecdotes, like the one about Lloyd George. Now a federal judge, this lifelong teetotaler was working as a lifeguard at the Sands in 1953 while still in school and was asked to bring Sinatra and his entourage “four chairs and a screwdriver.” George grabbed the chairs but was soon panic-stricken when he realized that the tool was nowhere to be found (it was a pool deck, after all). Chagrined, he returned to the singer, only to be told, a little roughly, that Sinatra wanted four beers and a screwdriver—the vodka and orange juice kind. Some lessons you have to learn the hard way.

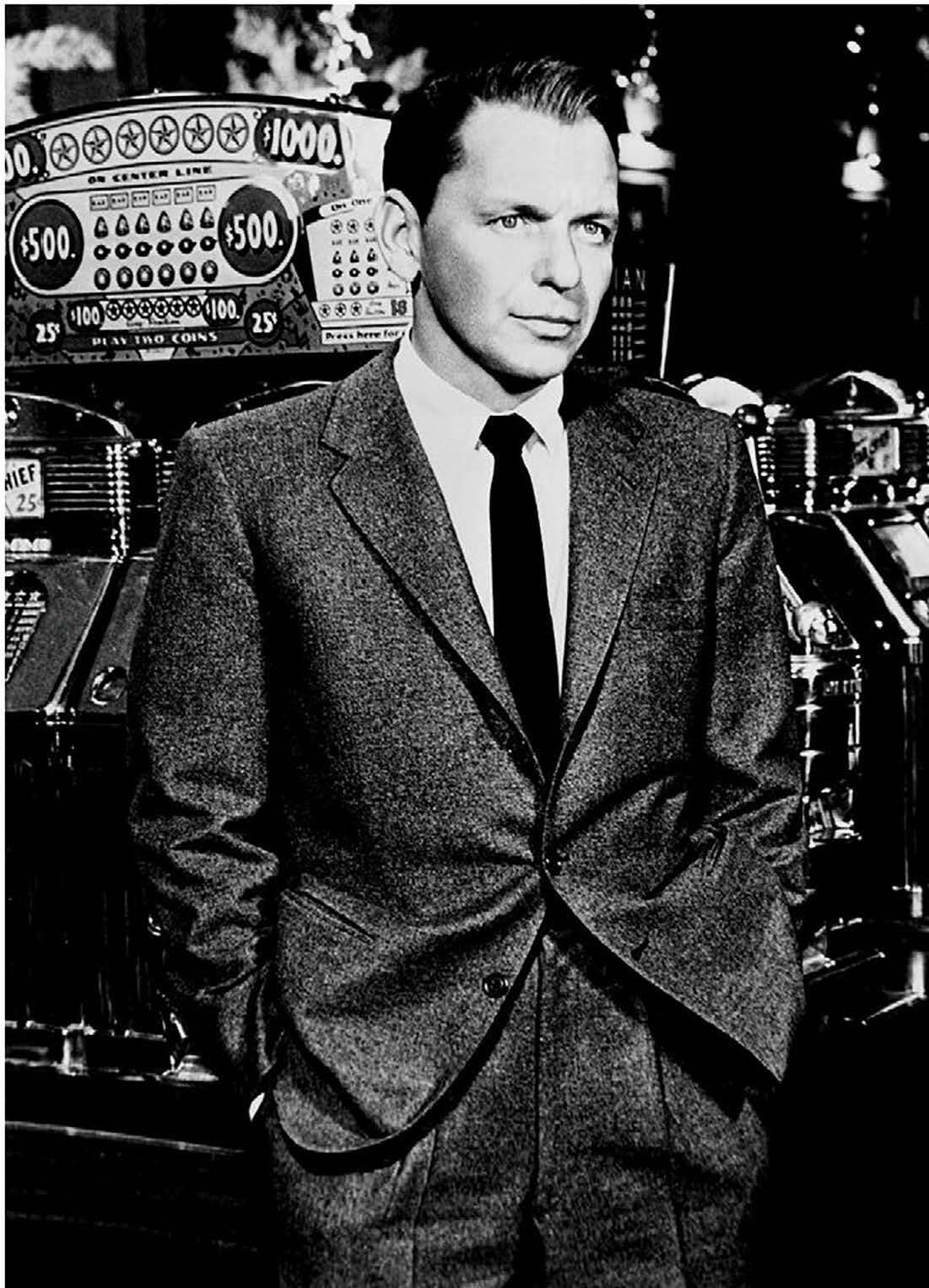

In the early ’40s, the skinny kid from Hoboken and Tommy Dorsey’s band was playing sold-out shows to swooning bobby- soxers at the Paramount in New York City for weeks on end. But a lot can change in 10 years, and when the 35-year-old Sinatra stepped out onto the stage of the Desert Inn’s 450-seat Painted Desert Room in September 1951, he was a different man—a man whose career had stalled and whose bank account was dwindling. “For six bucks, you got a filet mignon dinner and me,” Sinatra recalled of his first Las Vegas engagement in a 1992 interview. In his initial shows, the singer struggled with “Vegas throat” while serenading half-filled rooms of 10-gallon hats—freshly minted cattle ranchers and oilmen. But the boots and bolos wouldn’t last long.

“He brought the suits to town,” says Lorraine Hunt-Bono, a former lieutenant governor of Nevada, who comes from a family of Vegas restaurateurs and grew up attending Sinatra’s shows at the Sands. As a wide-eyed girl, Hunt-Bono caught her first glimpse of Sinatra and friends on stage wearing not cowboy boots but shiny patent-leather loafers. “They had these gorgeous-looking tuxedos, with the white stiff collars and the cuff links,” she says, “and when they walked out, I was like, Where did these guys come from? Oh, I fell in love.”

RESERVE YOUR TABLE AT SINATRA TODAY

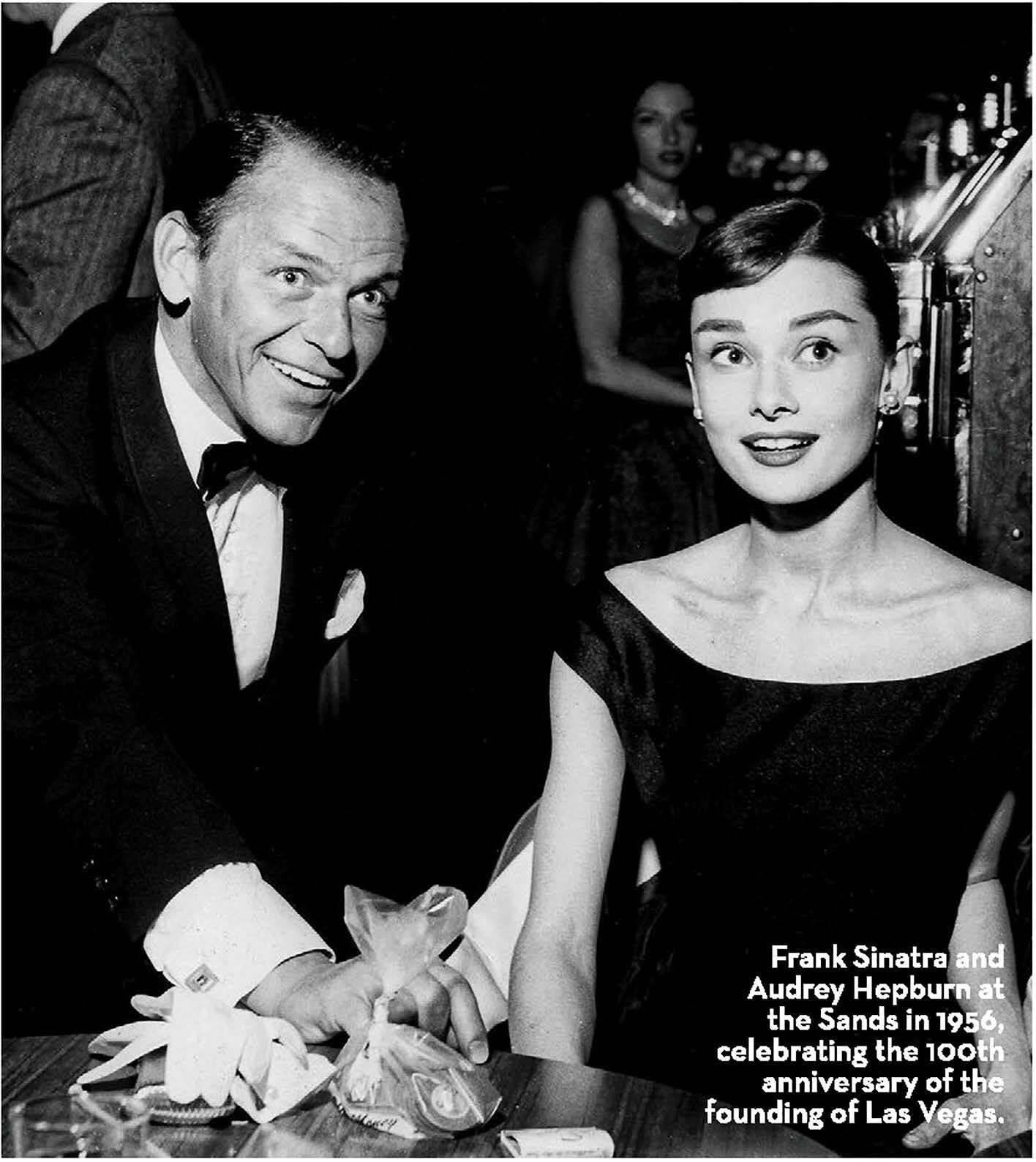

By early 1954—after winning an Academy Award for his performance in From Here to Eternity and embarking on a new collaboration at Capitol Records with arranger Nelson Riddle, which would produce the classic album Songs for Young Lovers and hits such as “I’ve Got the World on a String”—Sinatra returned to Vegas a conquering hero, even while his second marriage, to Ava Gardner, was fizzling. That year he purchased a 2 percent interest in the Sands Hotel, where he would remain a fixture for almost 15 years, cultivating his image as a hard-living, fun-loving swinger and giving some of the best performances of his career.

“The Copa Room held about 600 people, which today seems tiny,” says Michael Green, an associate professor of history at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, “but it also meant that it was an intimate setting, which certainly was conducive Sinatra’s rediscovery as a balladeer.”

In the early ’60s, the second coming of the Rat Pack (after Humphrey Bogart’s original crew; Lauren Bacall is often crediting with coining the term)—consisting of Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop—would forever change the notion of entertainment in Las Vegas. Inspired by the after-hours antics of the casino lounge shows, in which the mood was light, the drinks were plentiful, and improvisation was welcome, the Rat Pack sprayed seltzer, played jokes, and brought their star-studded audience into the act, while a well-stocked bar cart roamed the room.

As a teen, Hunt-Bono watched the mayhem from the wings. “Mr. Sinatra knew that I was a music major and that I loved to sing,” she recalls, “and he’d go, ‘Okay, honey, where are you going to sit tonight? You can either you can sit by the horns.’”

Wondering which Rat Packers would turn up at the Copa Room each night was part of the fun, with one well-known image of the Sands marquee showing the name of the headliner, Dean Martin, followed by the line “maybe Frank— maybe Sammy.”

Hunt-Bono remembers the night she and a friend were backstage watching Sinatra perform when Davis, dressed head to toe in a white janitor’s uniform, whispered, “Hey, girls, watch this!” “The audience is looking from the side,” she says, “and they see it’s Sammy’s face because he’s turned a certain way, and they all started to rumble. Frank’s going, ‘What the heck is this?’ and Sammy comes up to him and says, ‘Excuse me, sir! ’ And he starts sweeping up in front of Frank Sinatra.”

In early 1960, Hollywood’s elite—including Bob Hope and Lucille Ball, as well as future president John F. Kennedy—flocked to Las Vegas for a series of Rat Pack performances called the Summit at the Sands, which coincided with the filming of their Vegas-set heist film Ocean’s 11. According to Green, the “publicity bonanza” that resulted was a boon for both the Pack and Las Vegas.

But while the hotel was fending off the 18,000 reservation requests for its 200 rooms, the gang’s constant revelry took a toll on filming. After performing two shows in the Copa Room each evening, then partying and often performing again in the Sands lounge until the wee hours of the morning, the boys would sleep between shooting Ocean’s 11 scenes, then hit the steam room at 5 p.m. before doing it all again.

“This was an era when people smoke and drank, sometimes to excess,” says Green. “Frank represented that—doing the things that a supposedly full-blooded American male did. He became a symbol of an idealized Las Vegas. And Vegas gave him a degree of freedom he was unlikely to find elsewhere.”

“Frank became a symbol of an idealized Las Vegas. And Vegas gave him a degree of freedom he was unlikely to find elsewhere.” — Michael Green

Indeed, Sinatra’s bon vivant antics in the city are legendary. Roy Saunders, now General Manager of the restaurant Andrea’s at Encore, used to be the director of in-flight services on Wynn’s private planes and routinely made trips with Wynn and Sinatra between Las Vegas and Atlantic City. On one occasion, Saunders was asked to pick up Sinatra in Paris and return him to his home in Palm Springs. The old McDonnell Douglas MD-80 jet required two stops to refuel, and after a 13-hour trip to Paris, Saunders was met by the ramp agent, who informed him that Ol’ Blue Eyes had hopped on another plane five hours ago.

“But here’s the kicker: The airplane was very small, and he didn’t have room for his luggage, so it was all lined up on the ramp,” Saunders says with a laugh. So he ferried Sinatra’s 12 or so suitcases to Palm Springs, as instructed.

Sinatra would continue to perform in Las Vegas on and off until the end of his life. But the Vegas of the 1950s and ’60s was something else entirely—a brief, incandescent moment. Says Green, “It was a different time. It was a different town. And in a lot of ways, it was Frank’s town.”